Modern Administrative Regions of Jalisco

Emptying Town

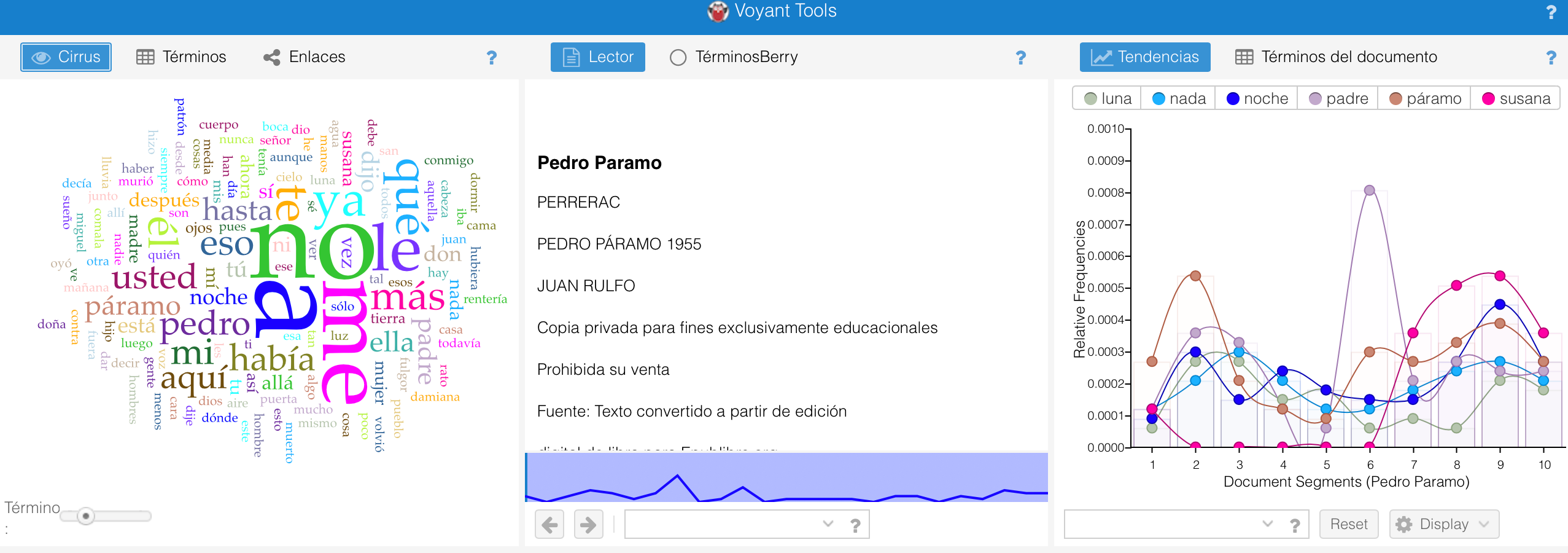

While Comala is a fictional town and seems to portray a fantastic and mysterious world where the dead still roam, it presents very real demographic changes happening in the southern region of Jalisco and the periphery of the state. If we look at figure 3 and the map in figure 4 we can begin to see that the region away from the center of the state and away for the center of power in Guadalajara suffered the most loss in populations- while the data in the CSV file is incomplete, it can be inferred that the trend in Jilotlán de los Dolores and Pihuamo, both located in the southeast section of the map to the left, is also applicable to the other municipios. Further development and access to the state census records would be needed to fully develop an exact picture of the effects of the war in the south.

Furthermore, Jilotlán de los Dolores and Pihuamo present lower concentration of haciendas. Given the economic importance of haciendas in the Jalisco economy and their higher survivability, the relatively small collection of haciendas in the 2 aforementioned municipios could imply 1) little economic development or lack of economic opportunity or 2) a monopolistic control of the land and economy by a handful of haciendas. The reduction of ranchos in the region could coincide with the collapse of of the extensive hacienda system following land redistribution after the Cristero War. Coupled with armed conflict in the region, it could be an explanation of the demographic change.