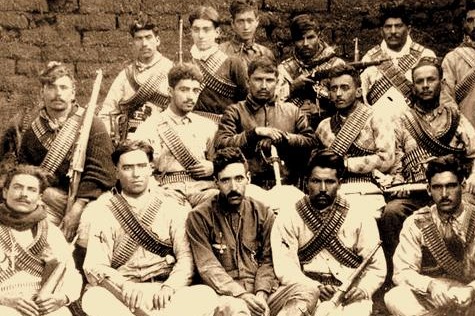

Cristeros before battle, 1928- unknown. Source: Google

The following section talks about the historical context of the Cristero War that contain graphic images that may be harmful and traumatizing to some audiences, viewer discretion advised.

Cristeros before battle, 1928- unknown. Source: Google

“Jalisco es México” or so the popular saying goes. The state of Jalisco and its unique mix of Spanish, French, and indigenous cultures has come to symbolize an archetypal image of what is Mexican both nationally and abroad. The State of Jalisco and its neighbors, composed by the states of Michoacán and Colima to the south, Nayarit and parts Zacatecas to the north, and Aguascalientes and parts Guanajuato collectively form what is known as Western Mexico, an area that shares a common history, peoples, and social values. A critical point in Western Mexico’s shared history, is the Cristero War (1926-1929). From 1926-1929, Western Mexico would find itself embroiled in a catastrophic religious war that decimated the region and destroyed rural communities, families, and lifestyles that had been in place for generations. The Cristero War (1926-1929) was a religious conflict, centered around western Mexico, in which the deeply conservative communities of the region rose up in armed conflict against President Plutarco Elías Calles (1924-1928) and the Federal Government.

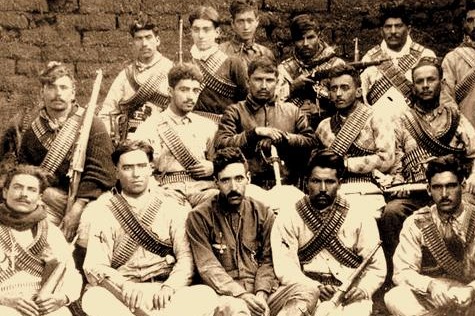

Extension of the Cristero War through out the Mexican Republic. Red areas are placed of extensive conflict- constitutes the bulk of Western Mexico

The reason for this was the 1917 Mexican Constitution, which required all clergymen in the country to register before the federal government or risk being deported or jailed. For many, this was seen as an affront to religious freedoms, and with the closing of all churches by order of the archbishops in Mexico, an attack on pre-revolutionary lifestyles that had largely remained intact during and after the Mexican revolution. The conflict was concentrated in Los Altos de Jalisco (Highlands of Jalisco), the southern region of Jalisco, and the state central and northern regions of the state of Michoacán. However, as Jean Meyer points out, the conflict was felt throughout Western Mexico. This war pitted the porfirianesque society of Jalisco against the Federal government and pro-revolutionary communities and families in the region, the conflict was brutal and traumatizing for the area. The trauma of the war, however, was never dealt with and was passed on from generation to generation; in fact, outside of Western Mexico, it’s as if the war never happened but within the region, it continues to be a festering wound.

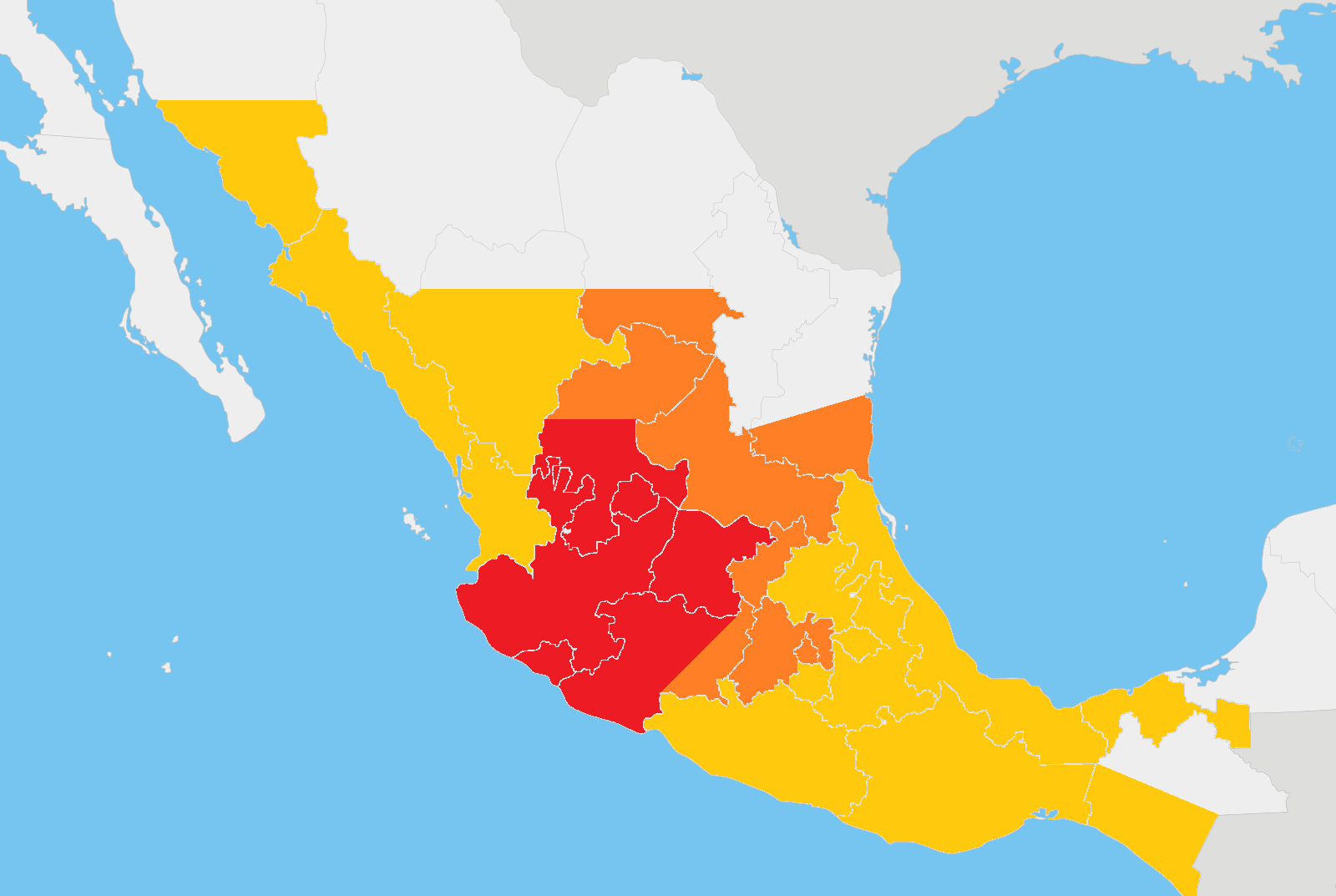

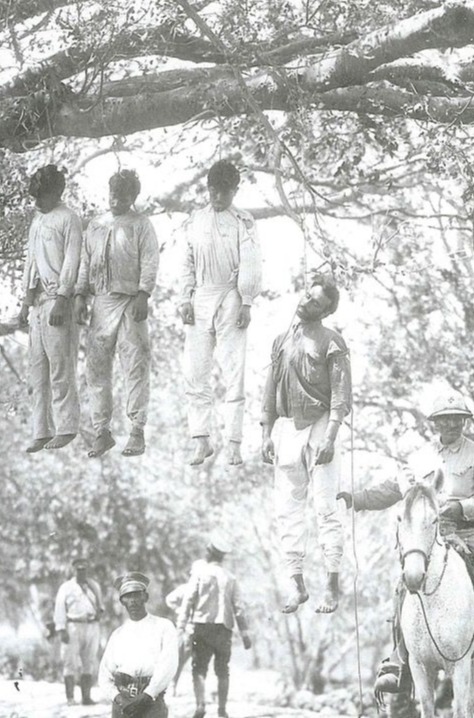

Catholics hanged by the Mexican government along railroad tracks near Zapotlán el Grande, in Jalisco. The media fallout from this photograph was so negative that President Calles later ordered the Secretary of War to hang people away from the train tracks in the future, almost prompted US Intervention. Hangings like these were common and located throughout the entire length of rail lines. However, it needed to be noted that acts like these were common on both sides

Cristero caught and hanged by federal troops

The Cristero War was profoundly traumatizing to the people that lived it, it turned neighbor against neighbor, brother against brother, and literally erased entire villages and towns- some were destroyed by the actual conflict and other were emptied due to the mass exodus from the countryside of those seeking a safe haven from the conflict to Guadalajara and other larger cities and towns in the region. It changed the landscape of western Mexico both physically and socially. Seeing your home and the land your family had existed on for generations suddenly empty can have a traumatic response on those that living the change and are forced to watch the decimation. It became daily life for those living during the conflict to witness death and conflict. This death was felt more heavily in the rural communities of Western Mexico where the Federal government and the Cristeros were essentially free to do what they saw fit. Cathy Caruth states: “Trauma is not locatable in the simple violent or original event in an individual's past, but rather in the way that its very unassimilated nature-- the way it was precisely not known in the first instance- returns to haunt the survivor later on “(4). It is possible that people that lived and saw their loved ones get killed and their communities destroyed, developed trauma. In figure 1, we can see that the map of Jalisco with a select number of municipalities highlighted in red. Deep/dark red indicted regions in which a large amount of ranchos were classified as uninhabited.

Figure 1: As you can see, the municipalities of Jilotlán de los Dolores, Pihuamo, Guachinango, and Hostotipaquillo suffered the largest increase in uninhabited towns. However, it must be noted that these municipalities also hold a larger percentage of rural towns as whole. Mascota and Villa Purificación also had a considerable loss in inhabited towns, but not to the ratio of the 4 previously mentioned municipalities.

Public hanging- 1928- Jalisco

Images like the one on the right, became common place in areas where the federal government classified the inhabitants and communities as Cristero's and against the ideals of the revolution. The traumatic experience of felt by the inhabitants, not just combatants but civilian, was severe enough to impulse an internal migration to safer areas (Meyer). General this meant migrating to larger regional cities like Guadalajara, Jalisco, Morelia, Michoacán, Mexico City, and some chose to immigrate to the United States. This new Western Mexican diaspora settled primarily in California, Texas, and parts of Illinois (Meyer). However, the question still remains, what was the impact of this sudden demographic change in rural Jalisco? The consequences of the war are far reaching, it had the possibility of slowing economic development in rural regions, which had the added affect of further exacerbating migration from the countryside. Furthermore, the Jalisco countryside, as well as much of Western Mexico, experienced a period of famine directly proceeding the Cristero War, as Jean Meyer points out in El coraje cristero, a collection of firsthand accounts from Cristero combatants. These accounts talk about many faced after returning home from the war, remain in their famine-struck and destroyed communities or look for better pastures.

Figure 2- Click on the drop down menu to see the break down of Inhabited and Habited settlement

Well if you look at the type of settlement and the amount inhabited and uninhabited, we start to see that ranchos suffered a larger population loss than the next largest settlement type, hacienda. Proportionally, municipios do have a larger concentration of ranchos, however, municipios with haciendas generally maintained a higher proportion of their settlements, with Guachinango being the outlier- this specific municipio had total of 7 inhabited haciendas (figure 1) and total of 141 inhabited and uninhabited ranchos. The municipio of Hostotipaquillo is also an outlier, it had a total of 9 haciendas but lost a large portion of its settlements. What the data in figure 2 tells us is interesting because, it shows that out of the entire dataset collected, only 3 haciendas out of 112 were marked as uninhabited as opposed to 365 uninhabited ranchos out of 1510 total ranches recorded in the dataset. This is an indication that economically powerful haciendas were able to whether the conflicts while ranchos, generally less economically powerful, suffered the greatest loss population. In the next section I will further develop haciendas and ranchos within the context of Jalisco and Juan Rulfo's novels.

Web page was built with Mobirise